Authors: Aboubacar Barry, Mariam Elbanna

Site of the publication : SUJM

Type of publication: Research paper

Date of publication: January 2025

Introduction

Islamic education in Guinea faces several challenges that hinder its full potential in promoting religious and social development. These challenges include limited access to quality educational resources, a lack of trained teachers, and the influence of poverty, which affects students’ ability to pursue education. Furthermore, there is often a gap between traditional Islamic education and the modern educational system, leading to a lack of integration with broader national development goals. Addressing these challenges is crucial for fostering a more inclusive and effective educational environment that aligns with both religious values and the needs of a rapidly changing society. Islamic education is a vital component of Guinea’s cultural and spiritual fabric, playing a central role in shaping the moral, ethical, and religious values of its population. Rooted in centuries-old traditions, this system aims to transmit Islamic knowledge, foster discipline, and uphold a strong sense of community among its adherents.

However, as the world becomes increasingly interconnected and the demand for a more versatile education systemgrows, Islamic education in Guinea faces challenges that threaten its relevance and effectiveness in addressing contemporary societal needs.This research delves into the multifaceted challenges confronting Islamic education in Guinea, examining their root causes and proposing potential pathways for reform.

A primary challenge lies in the inadequate infrastructure and limited resources available to Islamic educational institutions. Many schools operate in poorly equipped environments, with insufficient classrooms, outdated teaching materials, and a lack of basic facilities such as libraries and laboratories. This deficiency not only hampers the quality of education but also creates an environment where both teachers and students struggle to achieve their potential. Moreover, Islamic schools often rely on unstable financial support, such as community contributions or external donations, which are rarely sufficient to meet their growing needs.

Another pressing issue is the lack of qualified teachers who can balance traditional Islamic teachings with modern pedagogical approaches. Many educators in Islamic schools have received training focused solely on religious sciences, leaving them ill-prepared to teach subjects like science, technology, or critical thinking. This gap in teacher expertise exacerbates the already limited opportunities for students to acquire a well-rounded education that equips them for diverse roles in a modern workforce.

The curriculum in Islamic schools remains heavily focused on traditional religious studies, with limited emphasis on subjects such as mathematics, science, and technology. While these institutions succeed in imparting Islamic values, they often fail to provide students with the skills and knowledge necessary to navigate the demands of a globalized world. This lack of curricular integration creates a divide between Islamic education and the national education system, leaving students at a disadvantage when transitioning to higher education or competing in the job market. Addressing this issue requires balancing the preservation of Islamic traditions with the inclusion of subjects that foster critical thinking and practical skills.

Social and political factors also play a significant role in the challenges faced by Islamic education in Guinea. These schools often struggle with limited government support and recognition, resulting in insufficient funding and a lack of standardized policies. The marginalization of Islamic education further undermines its perceived value in society, leading many to view it as inferior to secular education.

Finally, the language barrier presents another obstacle to the accessibility and effectiveness of Islamic education. Many schools rely heavily on Arabic for instruction, which is not widely spoken by the general population. This linguistic disconnect alienates a significant portion of students and hinders their comprehension of the curriculum.

The findings of this study hold significant implications for educators, policymakers, and Islamic educational institutions in Guinea and similar contexts. The identification of core challenges—such as inadequate infrastructure, unqualified teaching staff, curriculum imbalance, and socio-political marginalization—underscores the urgent need for systemic reform in the country’s Islamic education sector. One of the key implications is the necessity for the Guinean government to recognize and support Islamic education as an integral part of national development. Increased funding, standardized regulation, and curriculum reform are essential steps toward enhancing both the quality and perception of Islamic education. Additionally, this study suggests that teacher training programs must be redesigned to encompass both traditional Islamic sciences and modern pedagogical approaches.

Results et discussion

The findings of this research illuminate the multifaceted challenges confronting Islamic education in Guinea, the exacerbating role of social, economic, and political factors, and potential strategies to address the deficiencies.

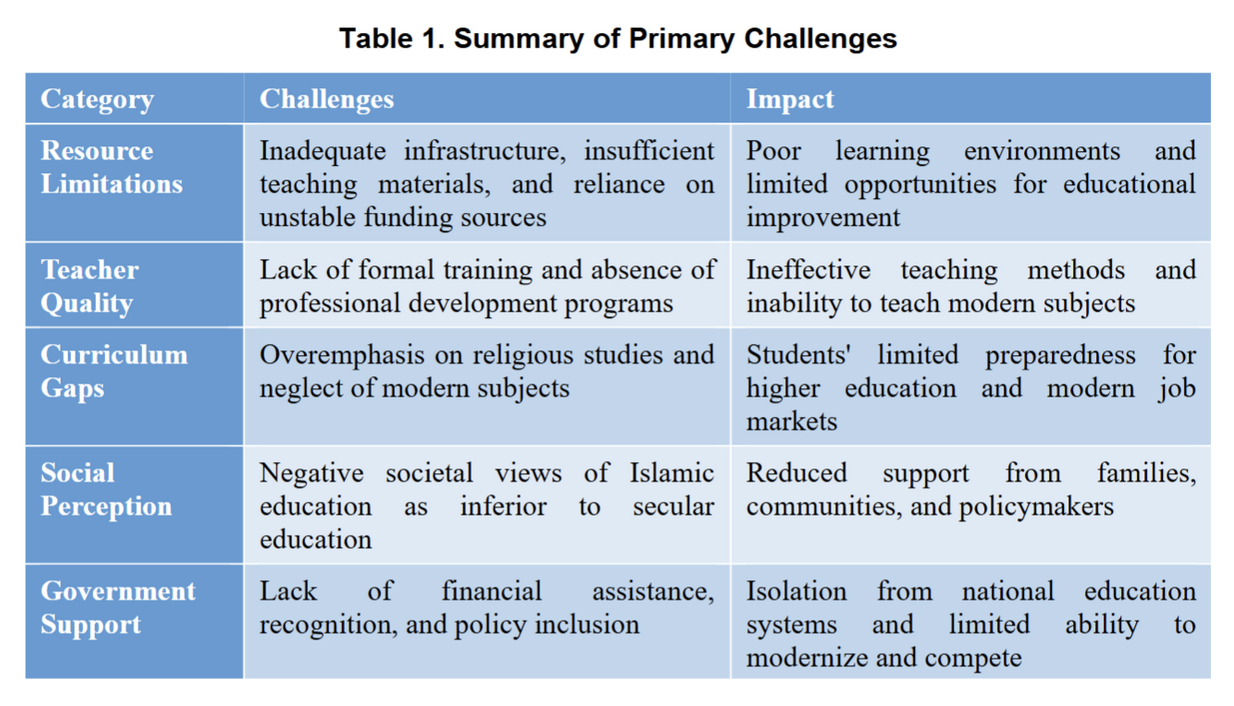

The study revealed several key challenges facing Islamic education in Guinea, categorized under resource constraints, curriculum issues, and societal perceptions. Economic hardships emerged as a pervasive issue, with 78% of survey respondents noting that Islamic schools operate on minimal budgets, relying predominantly on community contributions.

Curriculum inconsistencies also pose significant obstacles. Data from curriculum document analysis indicated wide variations between schools, with some offering limited secular subjects and others adhering strictly to Quranic memorization. Such disparities lead to unequal educational outcomes and reduce students’ ability to transition into higher education or the workforce. Additionally, gender disparities were prominent, as cultural norms in many regions continue to limit girls’ access to Islamic education, particularly beyond primary school.

The role of broader societal, economic, and political factors was evident in deepening the challenges faced by Islamic education. Economically, Guinea’s general poverty levels (with 43% of the population living below the poverty line, according to national statistics) directly affect the ability of communities to fund schools. Teachers’ low salaries, averaging less than $50 per month in rural areas, reflect this financial strain. Many educators reported taking on additional jobs to make ends meet, which detracts from their teaching effectiveness.

Socially, the perception of Islamic education as inferior to secular education contributes to its marginalization. Interviews with parents revealed a preference for enrolling their children in public schools, which are perceived to offer better prospects. A parent in Conakry stated, “Islamic education is important, but it doesn’t help my children get a job.” This sentiment underscores the need for Islamic schools to align their curricula with contemporary societal and economic demands.

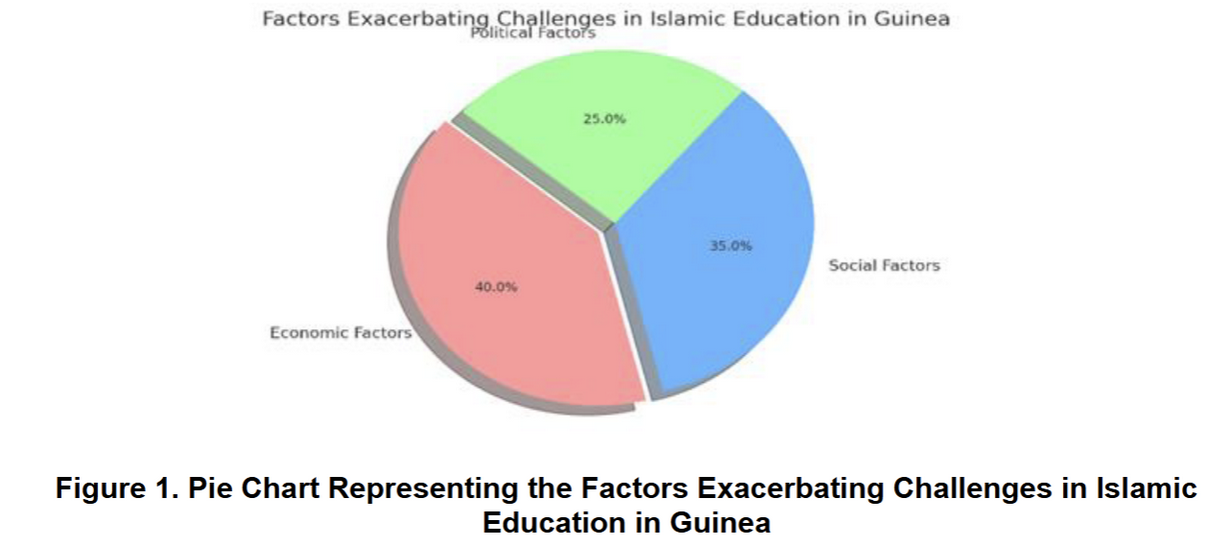

Here is a pie chart visually illustrating the distribution of societal, economic, and political factors exacerbating the challenges faced by Islamic education in Guinea. The chart shows how these three factors contribute to the overall situation. The sizes of the sections represent arbitrary percentage values, with economic factors having the largest impact, followed by social and political factors.

The research also explored strategies for improving Islamic education in Guinea, drawing on participant suggestions and successful examples from within the country. A recurring theme was the need for enhanced financial support. Stakeholders unanimously called for increased government funding, with 87% of survey respondents advocating for a dedicated budget for Islamic schools. Policymakers suggested that this funding could be used to improve infrastructure, provide teacher training, and develop standardized curricula.

Curriculum reform is essential to address inconsistencies and align Islamic education with modern needs. Teachers suggested that partnerships with national education authorities could help standardize curricula and provide access to resources. Furthermore, addressing gender disparities requires targeted efforts, such as community awareness campaigns and scholarships for girls.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the challenges facing Islamic education in Guinea are deeply influenced by economic, social, and political factors. Financial constraints, with a significant reliance on community funding and low teacher salaries, severely hinder the growth and quality of Islamic schools. Additionally, social perceptions that favor secular education over Islamic education further marginalize these institutions, limiting opportunities for students. Politically, inconsistent government support and a lack of coherent policies contribute to the ongoing challenges, with less than 10% of the national education budget allocated to Islamic education. However, there are potential solutions to address these deficiencies. Increased government investment, both in funding and policy support, is crucial to enhancing the quality of Islamic education. Community engagement and partnerships with NGOs can also help bridge resource gaps and improve teacher training.Furthermore, integrating modern curricula while preserving Islamic values could make Islamic education more relevant to contemporary societal needs.